The Artistic History of Hygiene

- Maya Ribeiro

- Jul 29, 2021

- 4 min read

If any of our readers are familiar with art history, particularly of the 17th Century- it is much closer to home than you might realize. There are interesting attributes to note- the fact that teeth are rarely painted, the pale almost sick look of most western skin, even down to the muddy colors used like browns and blues and yellows. There are a multitude of reasons why an artist may choose to express themselves the way they do, and interestingly enough, hygiene or lack of it in the 17th century has woven its way into a lot of art from the time Bathing

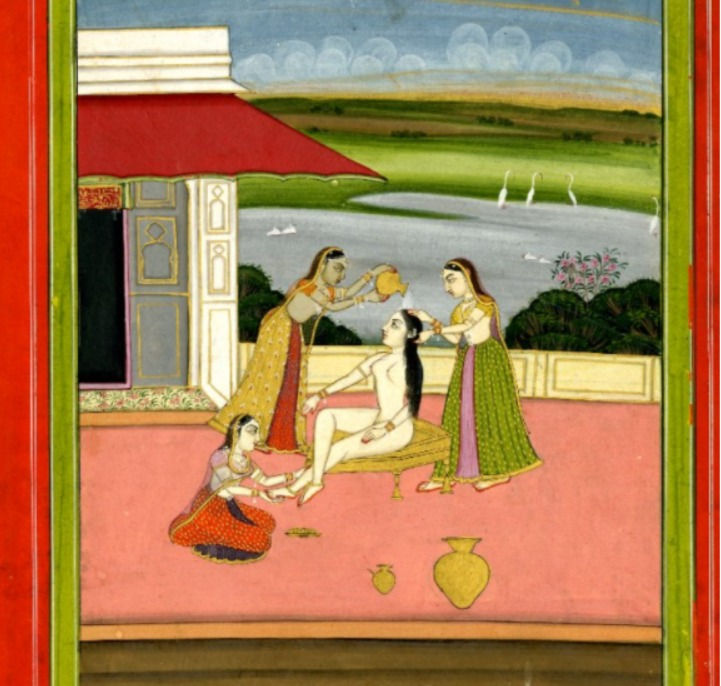

A common notion about the “olden days” is that bathing was considered a nonessential procedure, leading to body odor and general neglect. This is however very heavily dependent on the subcultures and subcontinents we choose to look at and study. During the 15th and 17th centuries in Japan, bathing became a widely popular cultural practice. Bathing in Japan has always been a part of rituals and religious practices, however, it now began to emerge with a more hygienic aspect, with a key focus on “staying clean” There are several depictions of Japanese people (primarily women), in bathhouses through a lot of Japan’s art

In Europe, at the same time, bathing was viewed as a spreader of infection and something that requires labor. Access to hot water and labor was a difficulty for most of Europe’s working class at the time, and therefore it was likely widely believed that bathing in warm water opened people’s pores up and made them more susceptible to disease. The alternative for most people was a kind of sponge bath. They would clean only certain parts of themselves or have water poured on them and cleaned off with herbs and other natural detergents.

Dental Care

Evidence of dentistry is found as far back as 7000 BC in art history. Good teeth and dental hygiene were valued in the 15th- 17th centuries, but that did not always mean they were taken proper care of. People used mouthwashes consisting of vinegar or rubbed herbs and cloth with tobacco ashes on their teeth as common dentistry practice. In one particular painting from the 18th Century, we see teeth being extracted from poor children to make dentures for the wealthy. While there is no real historical evidence to prove that this used to happen, it places emphasis on the need to have clean teeth during this era. Teeth transplants were apparently popular for a short while, however, implying that medicine and technology in the field was fairly advanced.

So is there really evidence of bad hygiene in art history?

Well, hygiene standards varied from country to country, but there was obviously a worldwide desire to take care of your appearance and to look your best in portraits, so the effects of poor hygiene on people’s appearances did not always show up in the artworks themselves. However, the 17th and 18th centuries were times of turmoil for most European Nations. The few paintings that do show teeth, especially of the lower socio-economic classes, have a prevalent theme of dirt and sickness. There is a visual distinction of poor from wealthy, with bad teeth often signifying lower economic standards and an inability to maintain personal cleanliness.

Interestingly enough, teeth were also often used to depict the effects of various diseases through a timeline of various infections, especially STD’s. Agnolo Bronzino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time (1546), for example, depicts an old woman (often called Jealousy) behind the figures in the foreground, whose bad teeth have led many to speculate that she represents the effects of syphilis.

Bacchino Malato (c. 1593), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio,

Italian painter Caravaggio’s famous self-portrait was created while he was ill for six months and doesn’t shy away from representing the poor state of his body. His yellow-ish skin shows signs of jaundice. Historians point out that his dirty fingernails and discoloured teeth (although not front and center) could have been common to the time and due to poor hygiene rather than disease.

The future

The word hygiene comes from Hygeia, the Greek goddess of health, who was the daughter of Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Since the arrival of the Industrial Revolution (c.1750-1850) and the discovery of the germ theory of disease in the second half of the nineteenth century, hygiene and sanitation have been at the forefront of the struggle against illness and disease. As art evolves, so do the ideas of what sanitation must look like in an ever changing societal backdrop.

This concept of being clean is not seen as “artistic” anymore, but cleanliness is a major part of the aesthetic awakening in the 21st century, which has been fuelled since the Renaissance. It is now a question of appeasing senses- From expensive fragrances for the nose to clean, neat study spaces.

Everyday, art gains a new meaning. Urban cities have seen the rise of Graffiti and street art. They resonate with people from different and diverse social backgrounds, create a sense of belonging, give new life and beauty to urban spaces and in some cases even act as powerful education and awareness raising tools. Hygiene and water sanitation are gaining momentum as campaigns rise to support these causes.

There is power in expression and power in what we choose to do with it. History has shown us this and as history repeats itself our art forms are changing and never looking like their forefathers. Hygiene is key for human growth and history tells us this over and over.

Stay safe!

Maya Ribeiro

SHARP

Comments